New Year, New Wood:How Trees and Woody Shrubs Grow

As we welcome a new year, it’s the perfect time to look closely at the quiet, steady growth happening right outside our windows. Woody plants — trees and shrubs — might seem static, but beneath their bark, remarkable processes are at work that allow them to thrive year after year.

What Makes a Tree Woody?

Woody plants differ from herbaceous (non-woody) plants in one key feature: the presence of wood. This wood is made primarily of lignified xylem cells, which give stems and trunks strength and durability. Unlike herbaceous plants that die back to the ground each year, woody plants persist, adding layers of wood that allow them to grow taller and wider over time.

How Trees Grow

Tree growth happens in two main ways:

Primary Growth: Occurs at the tips of roots and shoots, allowing the tree to grow taller or longer. It’s driven by the meristem, a specialized tissue that produces new cells.

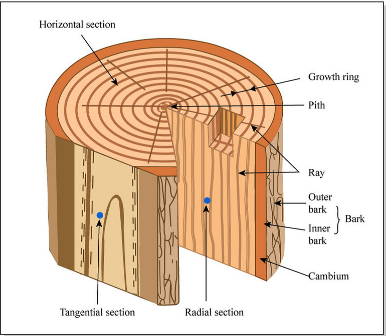

Secondary Growth: Happens in the vascular cambium, a thin layer just beneath the bark. It produces new xylem (wood) inward and phloem (bark) outward, increasing the tree’s girth.

The energy for this growth comes from stored nutrients (often from the previous year) as well as photosynthesis from the current season. Trees can tap into stored starches, sugars, and minerals to support early spring growth before leaves fully develop.

The Inner Workings of Wood

Wood is more than just a solid mass — it’s a complex structure that supports the tree and transports nutrients. Xylem cells provide both tensile strength (resisting pulling forces) and compressive strength (resisting squashing forces). Trees produce specialized wood in response to gravity or leaning. Compression wood forms on the lower side of leaning conifers, while tension wood forms on the upper side of leaning hardwoods, helping the tree maintain upright posture.

Fast vs. Slow Growth: What It Means for Tree Structure

Not all trees grow at the same pace, and the rate at which a tree produces new wood has a major impact on its structure and overall health. Fast-growing species, like the silver maple, put on large amounts of wood each year, producing long internodes and wider growth rings. While this allows them to reach maturity quickly, the wood is often softer and less dense, making branches more susceptible to breakage during storms. Slow-growing species, such as beech and oak, add wood more gradually, creating tight rings and dense, strong wood that supports a stable long-lasting structure. By knowing whether your trees are fast or slow growers, one can better understand their vigor, foresee potential weak points, and anticipate pruning cycles.

Aging a Tree

Understanding a tree’s age gives insight into its history, health, and growth patterns, but how can you age a tree?

- Counting Rings on the Trunk: Each year, most temperate trees produce a visible ring in their wood. By examining a cross-section of a removed tree, you can count these rings to determine its age.

- Using an Increment Borer: Dendrologists often use a tool called an increment borer, which allows them to remove a small core of wood without cutting down the tree. This sample reveals the growth rings and provides data about growth rate and environmental conditions. Variations in ring width, fiber density, or branch internodal distance can tell us about past droughts, nutrient limitations, insect attacks, or other stresses.

- Branch Growth: For smaller branches, you can observe the internodal spaces — the distances between leaf or bud scars along a twig. A long space indicates vigorous growth in a season, while tightly stacked nodes suggest slower growth or stress.

Observing Growth in Your Yard

You don’t need a lab to appreciate a tree’s growth — just a keen eye and a little curiosity. This winter, take a closer look at the twigs and buds on your favorite trees or shrubs. Notice the internodes, the spaces between leaf or bud scars along each branch. Healthy internodes are evenly spaced and often longer, indicating strong, vigorous growth from the previous season. Short, stacked, or irregular internodes can signal stress, disease, or nutrient deficiencies.

At Monster Tree Service of Rochester, we encourage homeowners to observe these subtle signs of growth and tree health. By paying attention to internode patterns, branch vigor, and bud development, you can better understand your trees’ needs and spot potential issues before they become serious.

As we welcome a new year, remember that even when growth isn’t immediately visible, trees are quietly building strength and resilience. With a little observation and care, the quietest branches and sturdiest trunks can tell a story of survival, adaptation, and remarkable change.

Silver Maple Tree Highlight

Species: Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum)

Also called: water maple, soft maple, silverleaf maple

Lifespan: On average 100-130 years

ID features:

Height: mature height of 50-70 feet

Spread: 30-50 wide

Leaves: Simple, opposite leaves are medium green, about 3 to 6 inches long, five-lobed, with silvery underside. Leaves are green in summer, turning yellow-green in fall.

Bark: Young bark is smooth and gray and eventually develops long, wide strips that turn upward at the ends as the tree ages.

Flower: Small, reddish-purple flowers that appear in early spring before the leaves emerge. The flowers are unisexual, with male and female flowers. These early blooms provide an important early season food source for pollinators.

Fruit/Seed: Winged seeds, called samaras, which are green and changes to light brown. They are formed in pairs. Each samara has a single seed with a long, flat wing, allowing it to spin and be carried by the wind, often dispersing several hundred feet from the parent tree.

Fun facts:

- Silver maple wood was once widely used for furniture, flooring, and musical instruments, valued for its light color and easy workability — though softer than sugar maple.

- In the late 1800s and early 1900s, silver maple was one of the most popular street trees planted across America. It grew fast and provided quick shade. Many older neighborhoods still have towering silver maples lining their streets today.

- Silver maple sap can be used for syrup production, though it’s thinner and less sweet than that of the sugar maple. It was historically tapped as an early spring sweetener source by settlers and Indigenous peoples.

Need to know:

Room to Root: Silver maples develop long, surface-level roots that can extend far beyond the canopy drip line. These roots help the tree stabilize in wet soils, but can lift sidewalks or compete with lawns for water. Give them plenty of space to spread naturally.

Ask the Arborist

ISA Certified Arborist: NY 6774A

NYSDEC Category 3A, 2 Certified Applicator: C8890526

Q: Why is it important for an arborist to know the tree species before making any cuts?

A: Different tree species have different types of wood and bark, and that affects how they react when cut. Some trees have soft or brittle wood that can tear when being cut, while others have dense, strong fibers that hold together better during pruning. Certain species, like beech, also have bark that peels or tears if it is not cut correctly, and that can damage the remaining branches. Knowing the species helps the arborist choose the right technique so the branch comes off cleanly and the tree can compartmentalize properly.

Q: How can observing annual twig growth (internode spacing) help diagnose early signs of stress before major symptoms appear in the canopy or trunk?

A: The distance between last year’s buds — called the internode — tells you how much a branch grew in a season. If the spaces are long and even, the tree likely had a healthy year. If the spaces are short, uneven, or tightly stacked, the tree may be dealing with stress such as drought, poor soil, root damage, or pests. This gives homeowners an early warning before bigger problems — like thinning leaves or dead branches — start to show.

Q: How does an arborist’s understanding of a young tree’s natural growth habit guide structural pruning decisions that affect its long-term form and stability?

A: Every tree grows differently. Some grow fast and wide, some grow upright and narrow, and others grow slowly and steadily. Knowing a tree’s natural growth pattern helps the arborist shape it while it’s young so it develops strong, well-spaced branches. This prevents future problems like weak branch unions, heavy overextended limbs, or uneven weight that could break as the tree ages. Early, species-informed pruning sets the tree up for a stable and healthy life.